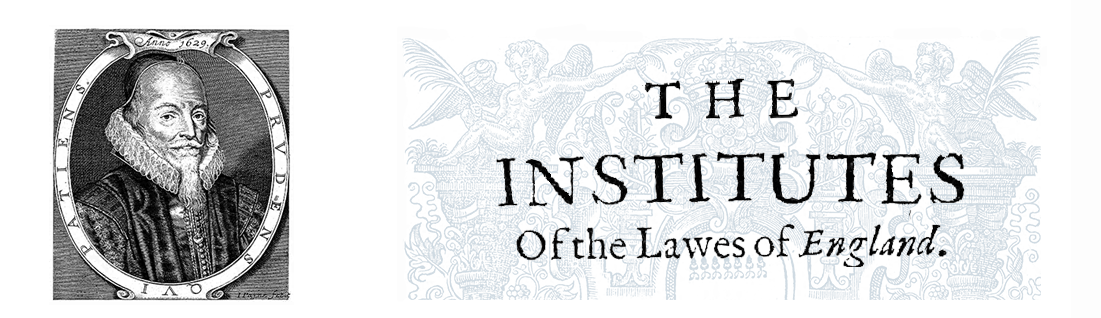

Besides a third edition of the first volume of the Institutes (the last edition published in Coke's lifetime), the Leon E. Bloch Library Sir Edward Coke Collection includes the first editions of volumes two through four of the Institutes, which were published shortly after their release by the Crown. The Institutes cover land tenures (Vol. 1), ancient charters and statutes (Vol. 2), treason (Vol. 3), and jurisdiction of the courts (Vol. 4). The Institutes were meant to be a way, really a process, for law students to immerse themselves in the common law. Consequently, they are important not only as a reference source but as a means to understand legal education in England and America. Indeed, this library's edition of Volume One has marginalia and markings that may date to the late seventeenth century. See e.g. fol. 19a. In 1769, American revolutionary and Supreme Court Justice John Rutledge would advise his brother Edward (a signer of the Declaration of Independence):

"[W]ith regard to particular law books Coke's Institutes seem to be almost the foundation of our law. These you must read over and over, with the greatest attention, and not quit him till you understand him thoroughly, and have made your own everything in him, which is worth taking out. . . . ."

-- John Belton O.Neall, 2 Biographical Sketches of the Bench and Bar of South Carolina 124 (Charleston, S.G. Courtenay & Co. 1859).

The Institutes were a revolution in their own right. First, breaking with tradition, they were published in English, making them accessible to a much broader audience. Second, Lord Coke made use of Littleton's Tenures, a book beloved of the English bar, for which he provided commentary. The resulting work was reminiscent of the glossed treatises of Justinian. See fol. 1a. Third, Lord Coke used extensive citations to primary law, authoritative commentary and the Bible. See fol 1b. These citations were pinpointed to exact passages, an innovation only possible with printed law books. The whole effect is "weight of authority," a tradition evident in modern legal texts. Finally, Lord Coke appealed not to the Monarch for approval (as earlier treatises had done), but to the reader, that he "will not conceive any opinion against any part of this painfull and large Volume, untill hee shall have advisedly read over the whole, and diligently serched out and well considered of the severall Authorities, Proofes, and Reassons which wee have cited and set downe for warrant and confirmation of our opinions thorow out this whole work.." See p. ix of the preface.